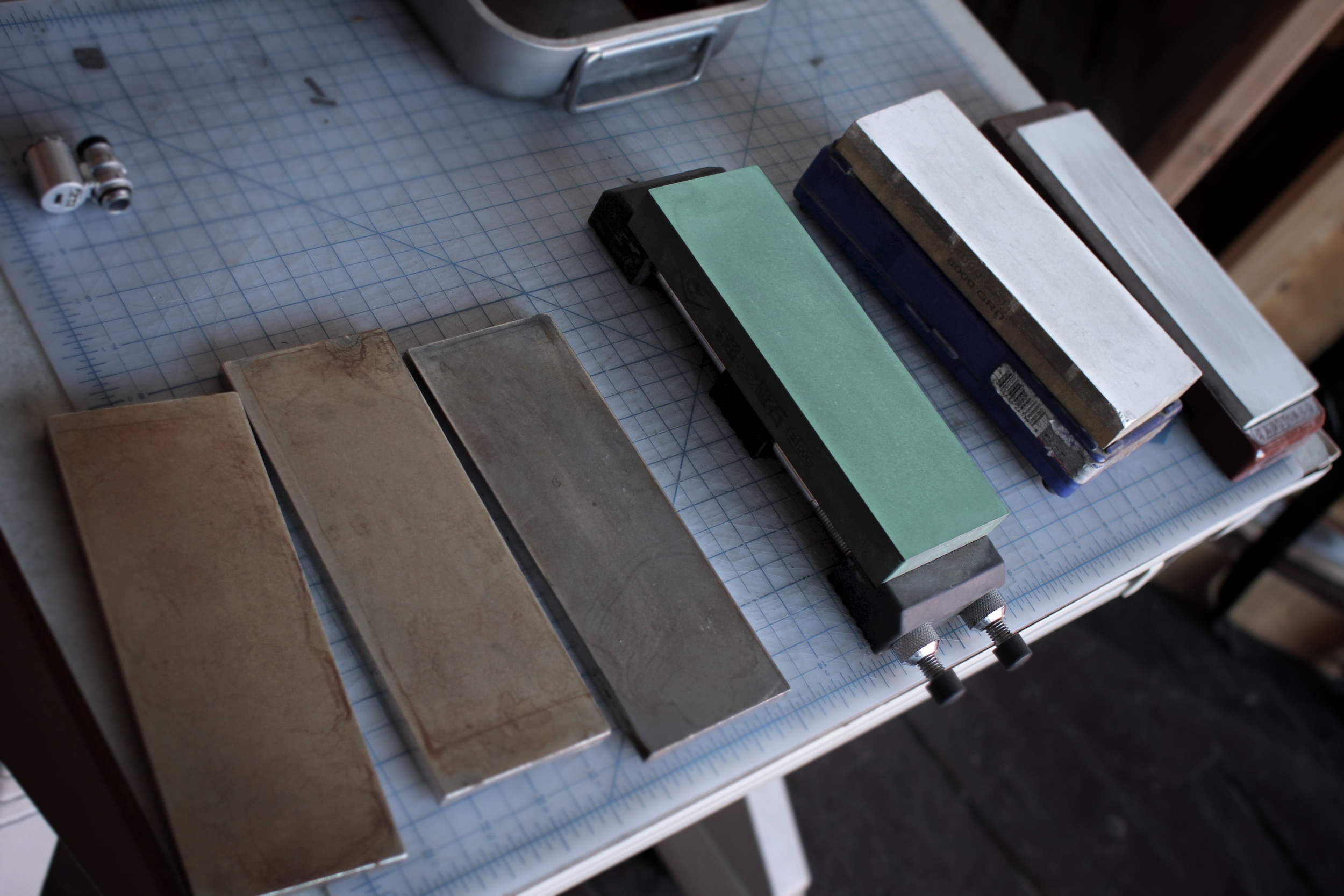

Our Straight Razor Sharpening Hone Progression: updated 8/21/2019

DMT Dia-Sharp Extra Coarse diamond stone - lapping plate for 400 & 1000 grit hones

DMT Dia-Sharp Course diamond stone - lapping plate for 4K+ hones

Naniwa Professional 400 - bevel setting

Naniwa Chosera/Professional 1K - bevel setting and honing

Norton 4k

Norton 8k

Naniwa 12k

Chromium Oxide pasted poly strop

Poly strop

Hanging Hair Test

Setup

We don't mind getting our table tops wet and covered in metal dust, so our setup utilizes individual stone holders and a spray bottle UPDATE: We now have a dedicated honing station with running water.

Bevel Angle

The angle of the bevel is determined by the height difference from spine to the edge on the razor. A little geometry is required to illustrate this: by changing either the thickness of the spine or the width of the blade, you can manipulate the angle of the cutting bevel as it sits on the hone. A thicker spine in relation to blade width will result in a steeper, more open bevel angle. A wider blade in relation to the spine will create a more acute, or closed bevel.

Putting this geometry into practice is quite simple: just set the razor flat on its side on top of the stone. We use 7/32" thick steel stock for 6/8 blades to achieve the proper bevel angle. We apply one layer of Super 88 electrical tape to the razor's spine for the factory hone, as this sets the ideal starting angle for the bevel and protects the spine (we don't feel the razor should arrive from the factory with visible hone marks). UPDATE 10/23/2017: due to production changes, we now hone all of our production razors without tape.

1. Bevel Setting. Setting the initial bevel on a straight razor lays the foundation for all the following steps by establishing the cutting bevel's angle. At this step, we are grinding either side of the blade down evenly until they meet in the middle, creating a continuous cutting surface the length of the blade. The goal is to remove a lot of material quickly, but evenly. Starting on the Extra Coarse DMT stone (now the Naniwa 400), we do this by alternating between small circle strokes with the spine elevated OFF the hone, and longer circle strokes with the spine ON the hone. It's useful to think of the edge as several different parts: ultimately, we want to be removing material from the very edge (front of the razor as it travels across the hone), but any material we remove from the edge must also be removed behind it (the flat surface of the bevel). In bevel setting, we find it best to knock down material at the front first by elevating the spine and to follow up with longer circle strokes with the spine on the hone to flatten the face of the bevel.

2. Bevel Setting cont'd. We transition to the Coarse DMT (now Naniwa 1K) when we can still see a hair-thin reflection along the edge using a flashlight--we call this the "Shine Test". The bevel is almost set, and so we don't elevate the spine off the stone during circle strokes much, if at all. We continue until there is no reflection along the entire edge of the razor, passing the Shine Test. The razor can pop hairs at this point, but the bevel is very rough and needs to be smoothed and polished with increasingly finer stones.

3, 4, 5. Honing. After the initial bevel angle has been established, honing can begin. We start on the Naniwa 1K, and move up to the next stone once all the hone lines from the previous stone have been smoothed on the bevel and it has an even shine. If we are honing a razor that has been in use for some time, we can usually start on the Norton 4K stone. However, razors with visible nicks on the edge will start on the Naniwa 1K, or even the DMT coarse if wear is extensive enough.

We use deliberate X-pattern honing strokes (push away, flip over the spine, pull back, with the blade travelling diagonally across the stone drawing an "X"). Some stones are narrower than the length of the blade, and so the diagonal path of the stroke ensures that the whole blade passes evenly over the stone. However, this means that the heel will come off the stone, and we have to be especially careful not to apply pressure to the heel as it passes off the stone, as this will cause a problematic groove on the bevel.

We sometimes vary our stroke, using 3-4 strokes of each and assessing how the blade is behaving. For example:

Apply pressure heel-to-toe as it passes across the hone. This is especially handy on smiling blades, but also helps sharpen the toe and heel of the razor more quickly. We make sure to pass evenly and seamlessly from heel to toe during the stroke, applying pressure as a wave that rolls from one hand to the other.

J-stroke. Draw a "J" as the razor passes down the hone. We combine this with heel-to-toe for added variance.

(Almost) elevate the spine. Apply rotational torque so the spine aaaaalmost comes off the hone, but doesn't. Here, we can feel pressure transition on to the very cutting edge of the blade, much like bevel setting. We are essentially trying to do the same thing; remove material at the front of the edge before flattening the face of the bevel behind it. We sometimes combine this with a stroke that draws straight down the hone to address the middle of the blade more directly.

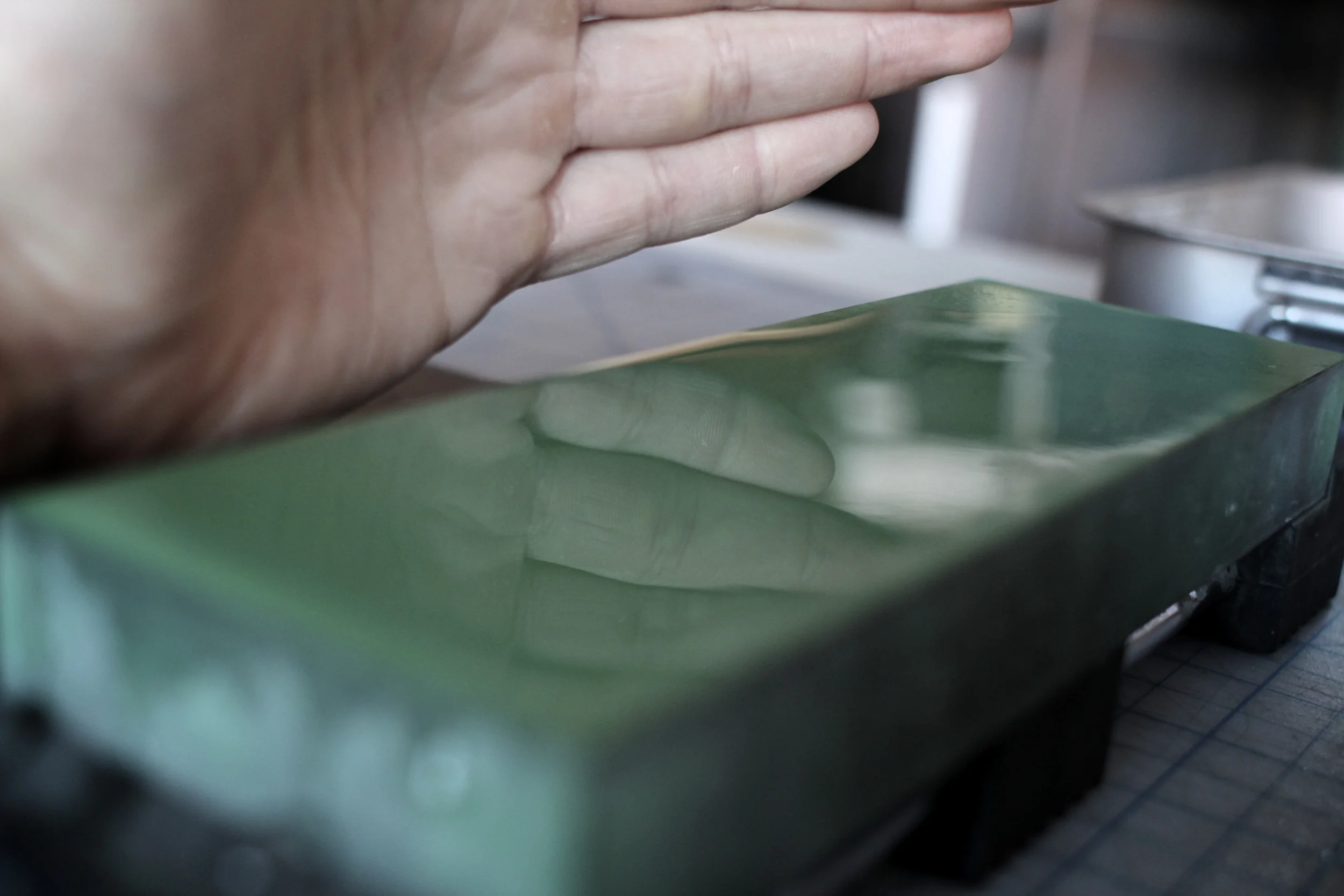

6. Polishing. The Naniwa 12K Super Stone has it's own gravity. When the stone is lapped level and has the right amount of water on it, it will just grab the razor and make it perfect. We use very light pressure to move the razor across the hone, and let the stone pull the razor in and do its work. This is our finishing stone and produces the final cutting edge and polish that makes our razors truly Shave-Ready.

7. Polishing on Pasted Strop. Some shavers like paste, some do not. Well, we like it a lot, and will do a good 20-40 passes on it before sending a blade out the door. Chromium Oxide polishes the bevel and smooooooths that edge just the finest amount without removing much material, while also keening the edge.

8. Stropping. How well we strop the razor can determine whether or not it will pass Hanging Hair. We strop on nylon for 100+ passes. You'll notice we do not normally strop on leather as part of our honing process. This is because we get comparable results going straight from the nylon to shaving as with leather, although stropping on leather can certainly get you an extra 10% in performance.

9. Hanging Hair Test. We test along the entire length of the razor, cutting a hair unsupported at least 1/2" out. We are looking for dull spots where the hair just slides off the edge instead of exploding... and I do mean exploding! The hair makes an audible "pop" when the blade is sharp enough.

If you're trying this at home, step 10 is to lather up and shave with it!

We hope you have enjoyed this series, and thank you for taking the time to learn more about our craft. If you want to learn even more about honing, email us and ask about future class offerings at our shop in Portland, OR.